For the most part, the advertising of these past few decades has occupied a very visual space. Print ads, television commercials, billboards - they're all a part of our day-to-day imagery. And I'm interested in how this day-to-day imagery influences our thinking, and in turn, our actions - because even if we're not hyper-aware of the particular ways that the totality of quotidian visual information - or we're not able to link specific images to specific thoughts - I can assure you that the link is still there, and the effect of advertising images is not trivial.

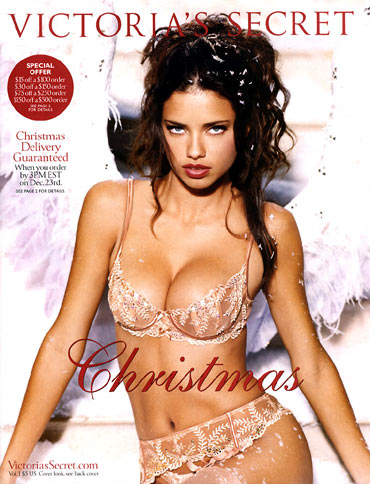

I'm going to use lingerie models to explain this.

Victoria's Secret was started in 1977 by Roy Raymond, who felt embarrassed when buying lingerie for his wife. Victoria's Secret was supposed to be a lingerie retailer that was comfortable for men to shop at, and it expanded from one store and a mail-order catalog to its chain store status today: there are more than 1000 Victoria's Secrets stores in the U.S. alone. But more than that, the models for Victoria's Secret (they're called "angels") are iconic: ask any college girl and they'll most likely be able to recognize at least one Victoria's Secret Angel and maybe tell you a first name as well. The Victoria's Secret annual fashion show (which happened a few weeks ago, coincidentally) is also a big deal. My point is, the image of the Victoria's Secret Model - deployed through mall advertising, online advertising, and mail order catalogs - is pervasive and very affective. And by affective, I mean that these Victoria's Secret ads affect how we think about women's bodies and essentially normalize a certain type of female body.

Of course, this type of female body is only one of many, and I'd say that it doesn't represent the majority of women's bodies. Tall, thin, huge breasts, long legs, blemish-free faces - but somehow, this type has been consecrated as an ideal? Why? I would argue that advertising is a form of normalizing images. Advertising sets standards, advertising affirms certain body types, and advertising gives cultural visibility to certain individuals. This cultural visibility can translate into public approval as well as public desire, and yet, public approval and public desire also feed into what is culturally visible - it's all a bit of a vicious cycle. We see celebrities in advertisements as much as individuals featured in advertisements become celebrities (e.g. the Subway guy who lost a lot of weight?).

I'm trying to think about how this all happens - and what gives advertising the authority to engage in such a determining process of normalization. It's irresistible in many ways, but also subversive. Women begin to hate their bodies and strive to look like Victoria's Secret Angels - not necessarily questioning where that desire for that Angel body comes from. Accepting the "types" we see in advertising as the standard, as the ideal is certainly blind acceptance, and this blind acceptance limits the acceptance of diversity, of difference, of other types. Because exclusive acceptance of one ideal is the rejection of so many others.

Advertising has given us a normalized definition of beauty and sexiness, but I think this can be changed by giving increased cultural visibility to a wide array of types and body types. So here's to the possibility of shorter Angels and larger Angels and squat Angels and curvier angels; to the possibility of more black Angels and Asian Angels and Hispanic angels. Advertising is normalizing, so why don't we normalize diversity?